The Colors of Shawa

Dear art seekers,

I am writing today’s newsletter from the ‘Jungle Fever’ cafe located on the rooftop of the Jordan National Gallery, where the painting of today’s artist resides, and where I currently intern.

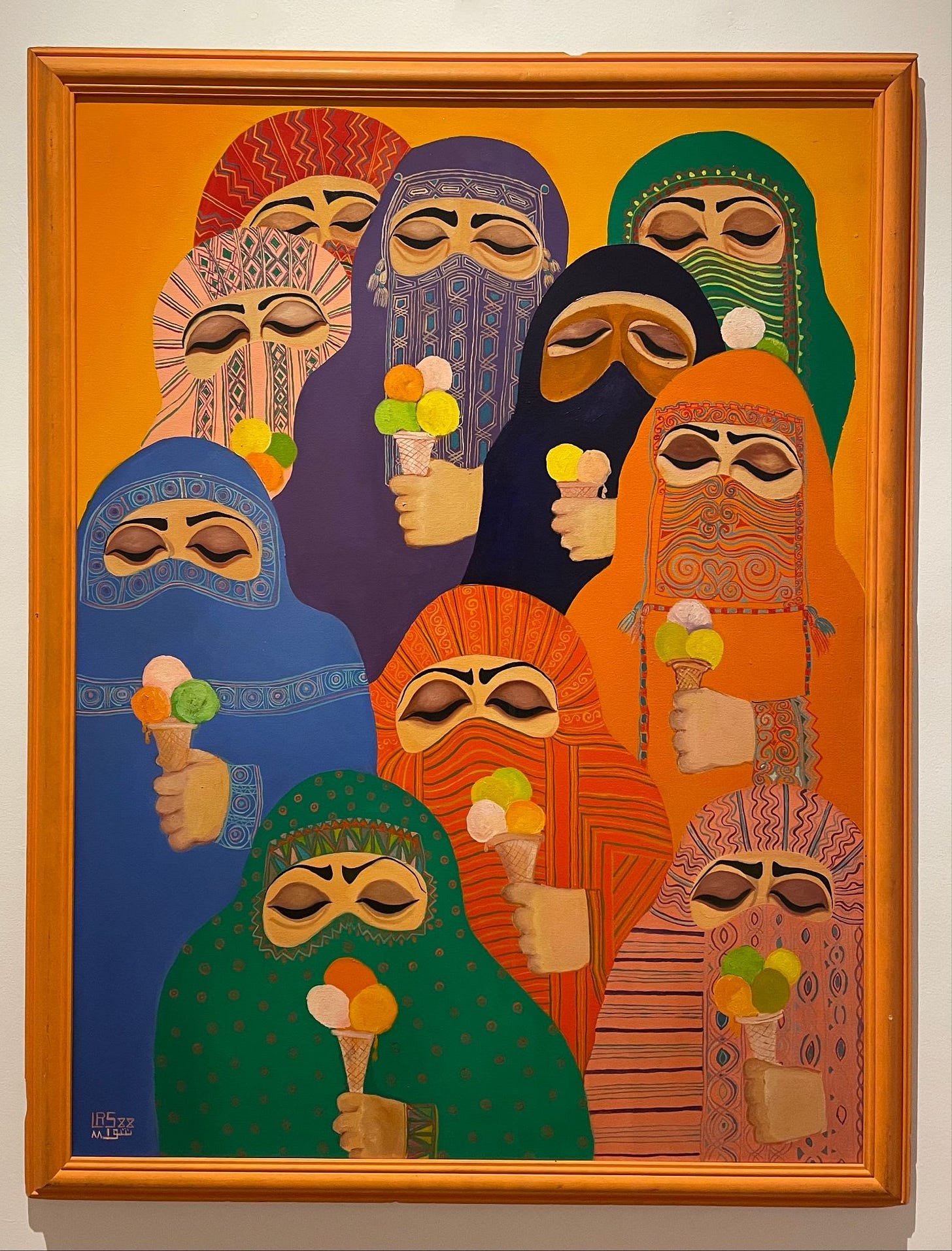

One of the first paintings that stood out to me during my first tour at the gallery was Laila Shawa’s Impossible Dream, 1988 (fig.1). Its exuberance highlights concepts beyond its bright colors.

Laila Shawa (born 1940, Gaza), a descendant of one of the oldest Palestinian landowning families, lives and works between London and Vermont. She received her first formal training at the Leonardo da Vinci Art Institute in Cairo in 1957–58. In 1958–64, she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, spending summers with the artist Oskar Kokoschka at his School of Seeing in Salzburg. She is one of the most prominent and prolific artists of the Arabic revolutionary contemporary art scene.

When she moved to London in 1987, she began a critique of the veil. The Impossible Dream depicts a group of women holding ice cream cones in front of veiled faces. It's humorous and provocative. But her practice goes beyond that, as Shawa explains in an interview with curator Samina Ali on Muslima. I’ve paraphrased parts of her interview below.

The Bidaa (veil) was introduced to Islam (possibly by the Byzantines in the late 7th Century), but has nothing to do with the teachings of Islam. The resurgence of the veil started with the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979 and spread into the Middle East. Its surge was more of a sociopolitical phenomenon designed to control and subdue women, the so-called weaker sex, as a result of men losing control of their lives due to Western hegemony and complicit and corrupt dictatorships.

When asked about the inspiration, she recalled an incident that elicited this series of work.

Palestinian women played a phenomenal role during the first Intifada (uprising) in 1987. Women stood up to Israeli soldiers while their husbands were hiding in fear of losing their jobs, as many of them worked in Israel as daily cheap labor. They defended their children and their husbands, which resulted in men losing their positions as heads of family. Because their resistance flipped the patriarchal order, and placed women in a position of temporary power, men lashed out and further encouraged the veiling of women, at least in Gaza, she explains..

While Shawa’s critique flips patriarchy on its head, her blame falls more on women’s compliance in reducing their status to an invisible state. Of course, many women also view the veil as a symbol of empowerment, and so this narrative is not so straightforward. Rather, it represents Shawa’s perspective, experience and understanding of history.

The painting Hands of Fatima, 1992 (fig.2), is part of the series called Women and Magic that observes a common practice of magic and witchcraft in the Middle East. Through this series, Shawa opens the floor to the discussion on how people leave the destiny of their faith to unknown powers. The evil eye that is intricately painted on hands covered in henna along with many detailed patterns and colors is meant to ward off evil from the envious.

Through her work, Shawa brings forth awareness towards feminism and deconstructing the patriarchal society. She brings to light the concept of power: through Western imperialism, men subjecting women to the veil and believers of the evil eye submitting to unknown witchcraft.. Hands have always been a symbol of power, whether to prove solidarity or defy it. In her painting Hands of Fatima, the hand is approached differently, as a way to resist what can be controlled, while still not being in a position of power.

Check out the rest of Laila Shawa’s work at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts.

Yours truly,

Rebecca