Rooted in Chaos

Dear friends,

“It is suicide to be abroad. But what it is to be at home, ... what it is to be at home? A lingering dissolution.” I was reminded of this Samuel Beckett quote while at a coffee shop the other day when the melodious voice of the famous Lebanese singer Fairouz started playing in the background. It is impossible to forget that you are not home, but it is especially painful when a glimpse of home comes to you.

In particular, I have noticed a cheery mood from taxi drivers upon discovering that I am Lebanese. In a recent encounter, a taxi driver went on ranting about Lebanon’s crises at 10:00 AM. I was not in the mood to start my day off like this and tried to let the morning traffic fill my ears instead. He later pointed out that my Lebanese accent wasn’t Jabaliye (mountainous) even though I am from the northern mountains - but what does he know!

For our subject today, I am bringing you close to home by discussing the work of the Lebanese artist Ayman Baalbaki, a personal favorite. I had the honor of meeting Baalbaki when he attended my final year exhibition at the American University of Beirut in May 2019, but I was so starstruck and intimidated that I probably forgot how to talk.

Born in Odeisse, Lebanon in 1975 - the year the Lebanese Civil War erupted (1975- 1990) - Ayman’s paintings reflect war events.

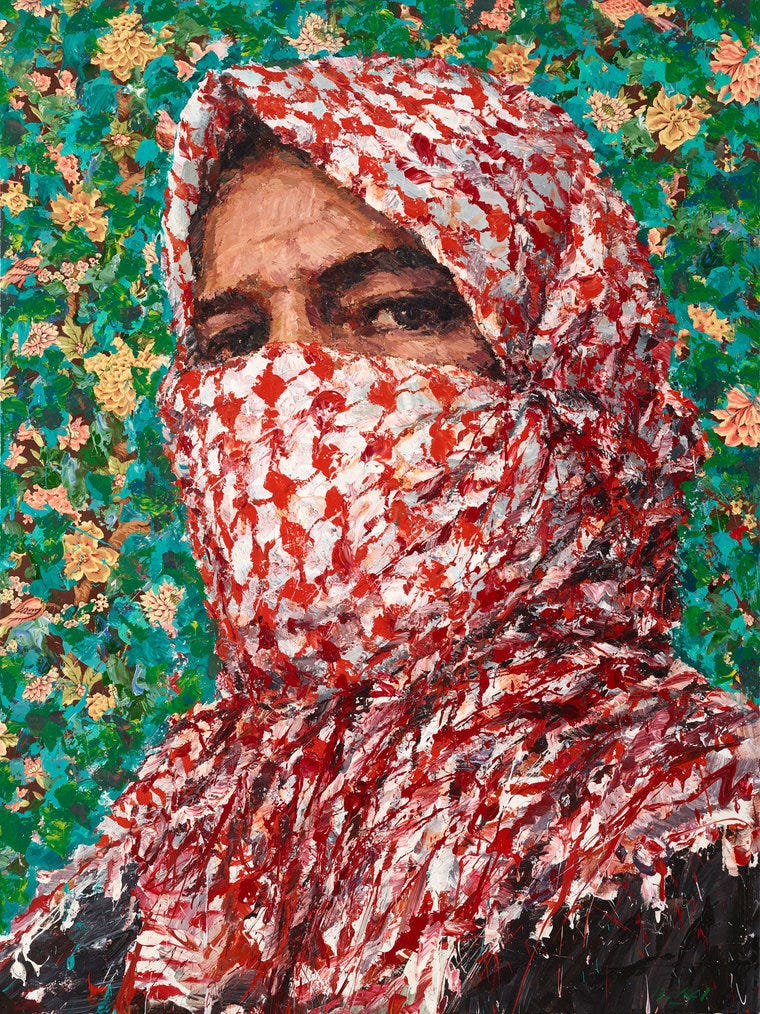

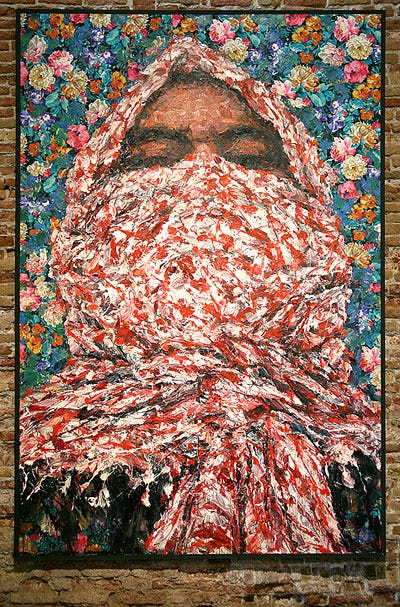

More specifically, his work is known for its small and large scale paintings of post-civil war buildings (fig.2) and warriors wearing veils or casks with flowery backgrounds. Ayman’s paintings have a presence that emits a sense of bleakness and destitute. At the same time, they invite viewers to immerse in it as they try to understand the words that the paintings are trying to speak.

His style and brushwork follow the content of his paintings. Upon taking a step back to analyze his work, undefined lines, splatters of thick paint and a full color palette come coherently together. This accentuates his formalistic approach through the primary emphasis on colors, shapes and forms. It seems quite suitable to chaotically paint a city of chaos.

But what is so mesmerizing about looking at the Al Mulatham (Veiled) (fig.1)painting? Is it the red and while scarf that has come to resemble the act of resistance and refuge? Or is it staring at the warrior’s eyes after we’ve got used to seeing them as passing figures on the news?

The colorful floral textiles backgrounds behind the warriors appear as an odd addition or rather as paradoxical. This imagery leaks in softness to the painting, adding a glimpse of hope of a re-blooming era that could erase the memory of the war. This imagery recalls the dresses worn by rural women in Southern Lebanon.

Ayman’s paintings invoke anger, anger of the past, present and future. More than a decade later and the artist is still painting destroyed buildings. His recent one was that of the Beirut Port Explosion on August 4th, 2020 (fig.3).

The artist draws inspiration from German Expressionism, Neo-Expressionism, and Abstract Expressionism or Tachisme.

Despite the power of Ayman’s work, I hope one day there won’t be a reason to paint about this never-ending chaos.

Yours truly,

Rebecca